At our program in April, National Poetry Month, we celebrated poetry written by women for women. Six local poets had come to share their talents with us: Minnie Bruce Pratt, Jennifer Jeffery, Georgia Popoff, Tania Ramalho, Marthe Reed and Jackie Warren Moore.

Chairs arranged in a large circle with the presenting poets interspersed among us made the group feel informal and supportive. Called upon in random order, each poet spoke about the importance writing has in her life and then read selections from her work. Three poets spoke, we took a refreshment break, and then three more shared their work. What a joy to listen to their stories and experience their insights through poetry!

Minnie Bruce Pratt said that she never meant to be a writer. She was raised by people who were afraid of the power of imagination and what it could lead to in terms of our bodies. Finding her reading a copy of The Scarlet Letter, her mother took the book away and made Minnie promise never to read it. Minnie believes that while there clearly is a difference between words and actions, there is an intimate connection between literature and the ideas it gives us. We do not have to act on these ideas, but we can sometimes act on them. Being with others can give us the strength to act and keep acting on new ideas that we choose to embrace. Minnie became involved with the liberation movements evolving at this time, especially women’s liberation. She came out as a lesbian in 1975, an action that cost her custody of her children but allowed her to fully come back to her physical body. For her, physical experience leads to the deepest writing; she now had the freedom to “write myself out of the past into the future.” Minnie read her poems: “The Great Migration” written in the voice of Beatrice, the African American main character who traveled North to escape discrimination in the South, “Standing in the Elevator,” “Epigraph” (the only danger is not going far enough), and “If We Jump.” Minnie generously gave a copy of her book Walking Back Up Depot Street to those wanted one.

Jennifer Jeffery told us that she thinks in poetry–for her it is a natural way of being. She grew up in a rural area where practicality was valued over poetic expression. She served in the military and is member of the Syracuse Veterans’ Writers Group. She finds deep reward in sharing her work with others. Jennifer writes because she believes a woman’s voice has just as much value as a man’s voice. Jennifer read her poems: “My Heart,” “The Crow” and “Home Safe” (both from a veteran’s perspective), and “I sat with the Dark This Morning.” The latter poem inspired a young veteran to finally share his own poetry with the writers’ group. Jennifer believes that we all have our “dark side” and we should acknowledge that death is a part of life. Her moving poem “Blue 8/12,” written as a series of letters, celebrates appreciating the everyday gifts loved ones leave us even after their deaths. She ended with “The Eternal Question,” a light poem about her pit bull, Puck.

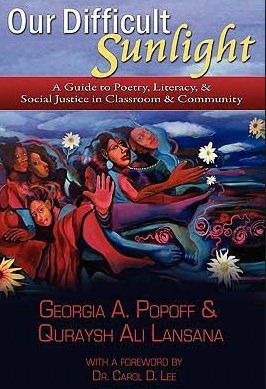

Georgia Popoff always knew she would be a poet. People told her she would not be able to earn a living at poetry; she held a series of other jobs, but wrote poems. In her thirties she experienced a “crisis of faith ” and was unable to write for 10 years. “If I can be of service with my words, can I please have them back,” implored. She regained her poetic voice in her forties, publishing The Doom Weaver, poems reflecting on her unaccomplished dreams. She read “Hog Nose Adder” and “Weight Not Carried” from this book. Georgia has worked as a poet in schools and helped teachers find ways to add poetry into their teaching. In 2011 she and co-author Quraysh Ali Lansana published Our Difficult Sunlight: A Guide to Poetry, Literacy, and Social Justice in the Classroom and Community. Georgia has a book coming out next year in which the poems are written in other voices because the poet can often say more things when speaking through other characters. Joy the Agnostic a is a central character in this work; it will have four cycles–in one Joy talks to the reader, another is her inner thoughts, another her outward “rants.” Georgia read”Confession” and “Outside Voice.” She is now working on another volume of poems influenced by psychometry or divination. This will also have four cycles: poems written by objects owned by iconic women; a cycle of letter poems written by fictitious women, “anonymous” voice poems, and “I am…” poems in Georgia’s own voice. She read a poem from the letter cycle in the voice of a Boston bombing victim and one from the object section in the voice of Bonnie Parker’s right glove. Georgia also read “Note from Aunt Jemima,” who was an American icon while the three black actresses who took on her persona over the years were basically invisible and unknown.

Tania Ramalho, friend of Shirley’s, Professor of Education at SUNY Oswego and proud grandmother, writes about “who I am and who I am becoming.” Born and raised in Brazil, she came to this country as a high school exchange student, returned here for her education, and decided to stay and become an American citizen or Brazilcano. Although she has written poems since she was a teenager in Brazil, she has only recently considered herself a “poet.” Involved with the women’s movement over the years and an active member of Syracuse Peace Council, she is part of a writers group at Oswego, where she shares poems that she writes when she is angry about injustice. A year and a half ago she finally said, “I am a poet.” She began writing political poems about when she decided to stay in the U.S. (Our government supported the dictator who ruled Brazil). Tania describes herself as a radical pacifist, angry at economic inequality, and really angry at what is going on the U.S. schools. Tania shared her poems “Connecticut 1981” about a feminist conference trip she took; “The Draw of the Luck” about thrift stores; “Education Reform Drone Teachers for Freedom”about restrictions on teachers’ creativity in the classroom; and “Apology to the Afghan People,” which was published in the Peace Council Newsletter. In response to the slogan “Freedom Is Not Free” used to justify war, Tania wrote a poem asserting “Freedom is an act of peace…an act of love that is entirely free.”

Marthe Reed is new to Syracuse having moved here from south Louisiana at the end of July. She has been a poet forever and written a number of poetry books. She describes her life as “nomadic:” She grew up in Escalon, a small farm town in California. From Bloomington, Indiana she and her family moved halfway around the world to western Australia before spending seven years in Louisiana. She read poems from Pleth,which she wrote in collaboration with transperson j. j. hastain. This work is about transcending boundaries: “The rules are what you think they are.” She shared some visual poetry collages by j.j. and her related text poems. She read portions of her work After Schwann. After reading Swan’s Way by Marcel Proust, about a man in love with a woman who had male and female lovers, Marthe “cut up” fragments of Proust’s text and wove them into a new poetic narrative. She also shared “Phillip Whalen’s Tulip” and poems inspired by Syracuse in fall and late summer.

Jackie Warren-Moore considers herself a “community writer.” She read her poem “The Speaking Lesson” from Growing up Girl. She comes from a long line of women speaking out. Jackie shared a story about her mother grabbing a tire iron to rescue an African American man who was being physically threatened by white men. At that point Jackie learned that her own weapon of choice would be words. “Your silence will not save you, so I speak.” She believes poetry cuts through all the things that keep us apart. Poetry opens hearts, opens hands, and establishes communication. Jackie read some poems written over the years. “The Women Gather,” “For the Children,” “Tightrope” (just us to break the tightrope of racial tension). “By Justin Who Loves Me” was inspired by her grandson saying,”Gigi, you are my big fat beautiful one.” “For Paula Cooper” speaks to violence begetting more violence. Jackie read her most widely published poem “Death Wish for Uncle Joe” about the sexual abuse of a young girl by her uncle. She also read “Games” and “Unlocking Midlife” published in an anthology Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number. From the anthology One Hundred Best African American Poems edited by Nicki Giovani, Jackie read her poem about AIDS, “She Wears Red.”

Moderator Shirley Wells thanked all the poets and expressed the sincere gratitude of the group for the privilege to share this experience. Six unique voices speaking their own individual truths yet seeking what is universal in our experiences as women.